Finalist, 2012 Indie Discovery Award in Memoir

Read Balcony View online at Issuu

Listen to an interview from the September 11th museum.

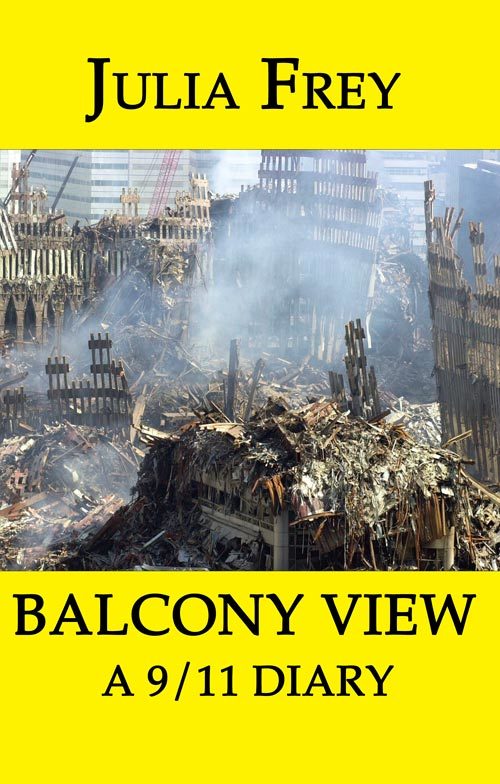

“What if you had a dying child, spouse, lover, parent, and the world caved in? It could happen. What was it like, after the Towers fell, to live in a war zone with a gravely ill husband? Julia Frey’s BALCONY VIEW is far more than a 9/11 story. In this unique, historic diary — the handwritten original is in the 9/11 Museum in New York — Frey, a distinguished biographer, found herself in the unenviable position of writing about a life as it was falling apart — her own. Her vivid, wry, tender book describes living for six months at Ground Zero with writer, Ron Sukenick during his terminal illness. It’s a beautifully written, clear-eyed portrait of simple courage, remarkable humor, generosity and decency.”

Douglas Penick, writer, literary critic

“Balcony View: A 9-11 Diary by Julia Frey, explores the aftermath of the World Trade attacks. Julia and her husband Ron live in a building directly across from Ground Zero. They are literally standing in the window as the first plane hits, watching chaos unfold. Ron is disabled, and the couple immediately wonders if they should even try to flee. Eventually they are evacuated, and Julia tells her story of what happens next. Living in Battery Park City at the most devastating time in NYC history, Julia is inundated with anxiety, illness and a close up look at death on a daily basis. Not only is the journey towards acceptance and recovery a terribly unbalanced, uphill battle, there is also a love triangle. Julia is in love with Malcolm, a man who lives abroad. Yet she loves her husband Ron too, and can’t abandon him—especially now. Will she stay or will she go? Will Julia and Ron be saved from the insanity that is Post 9-11 New York, or will they stay because it’s home? Readers get a Balcony View of what’s next, and this one is a stunner.”

“The view from this balcony is compelling and utterly unique. Julia Frey has a first row seat for the two tragedies which mark her existence — the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and her husband’s progressively disabling malady. She peers down at the excavation of Ground Zero and brings us an account both riveting and thoughtful, despairing and buoyant, graceful and frank. As she navigates post 9-11 Manhattan, and a marriage that has been dealt the blow of untimely illness, we get to see, up-close, how ordinary people get through extraordinary times. With her deft touch and her sharp-warm humor, Frey is the perfect guide for such daunting territory.”

Elizabeth Scarboro, author: My Foreign Cities

Very quietly Ron said, “You know, I think the Towers are going to go. Maybe we’d better get out of here.” If either of the Towers fell at a certain angle, our building was directly in the line of fall. Above the raging flames, the steel I-beams were beginning to bulge out, softening in the heat. Again his unnaturally quiet voice, “I can’t stay here. If the Towers start falling on us, I’ll die of fright.”

BALCONY VIEW – a 9/11/ Diary by Julia Frey

Julia Frey’s remarkable account begins on September 11, 2001, as the couple decide that no matter how weak Ron is, they must somehow flee. They abandon his wheelchair. He is too frail to climb on a boat. Later that day, covered with ashes, they struggle home through a neighborhood pitched into destruction and chaos, to look out his study window at their new view: “the stage-set for Dante’s Inferno.” The domino effect of one burning, collapsing building setting fire to the next one makes it clear that their own building could still go.

“The electricity was out. Ron could never go down 26 flights on his rear end. We were trapped in the sky.” That’s when Julia decides to write it all down — if only for the people who will find their bodies. Describing the first night in the the ruins, being evacuated, then returning weeks later, to live at Ground Zero, she discovers that their world has totally changed, yet finally not changed at all. “Our previous problems didn’t magically disappear. They were just waiting for us to come back in the door.”

This hugely powerful narrative of double coping — with Ron’s progressive illness and with the after-effects of 9/11 — describes a situation the manuals don’t cover — caregiving in a disaster. Her intense yet humorous ‘you are there’ style moves the diary swiftly along, catching us in a gripping, touching, brave, and yes, funny story of falling towers, a failing husband and a floundering ménage à trois. “Nothing happens in a vacuum,” she says, weaving in the leitmotif of a love affair. Unflinchingly, she faces the ruins outside and her frightening, inner ambivalence as she sacrifices creative and professional life to nurse her husband. Ron is no angel either — the self-centered, willful novelist insists she take a lover, then wants her to give him up. “What makes him think he can turn us off and on like televisions?” she wonders. In a poignant Coda, she describes an almost supernatural series of events after Ron dies. There is even a happy ending.

*****

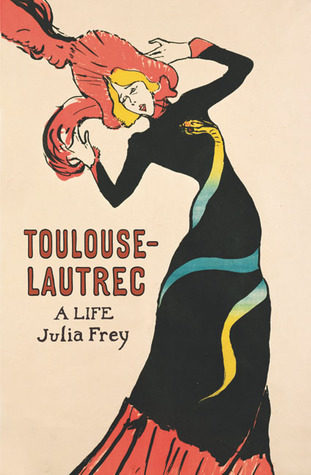

PEN West Award in Nonfiction, 1995

Finalist, National Book Critics Circle Award in Biography

NYTimes Notable Book of the year

Publisher’s Weekly:

“I expect to burn myself out by the time I’m forty,” vowed Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864-1901), whose alcoholism, sexual debauchery with prostitutes and probable syphilis led to his death in 1901 at age 36. In the fullest portrait of the great French artist to date (superbly illustrated with 84 photographs and 50 color plates), Frey traces Toulouse-Lautrec’s self-destructiveness to psychic pain resulting from congenital dwarfism and the conflicts of his parents-first cousins from a wealthy, aristocratic, inbred family-who used him as a pawn in their endless power struggle. The combination of a pious, overprotective, controlling mother and a grandiose, anti-clerical, manic-depressive father produced an ambivalent son who sought refuge in art. In oils, lithographs and posters, Lautrec penetrated people’s masks and exposed undercurrents of despair, poverty and exploitation beneath the Belle Epoque’s superficial gaiety. Drawing on hundreds of previously untapped letters and family documents, Frey, who teaches art and literature at the University of Colorado, has produced a vivid, engrossing, often astonishing biography that delves into Toulouse-Lautrec’s obsession with gems and hygiene, his mania for publicity, his love-hate relationship with his mother and troubled relations with other women.